Note: If you use RO/Distilled water, your residual alkalinity is zero. There’s nothing to buffer the pH in TDS zero water. This article is only for people that use at least part of their brewing water from the tap. This article won’t cover the full science of water chemistry. It is only intended to provide an overview. It’ll cover a process that I use. It’s one that I’ve had great results with. I know others that use the same or very close methods. This method is a very simple way to measuring and correct brewing water. you can use it to suit any beer style.

General considerations

If you’re all-grain brewing, you’ll probably get to the stage where you want to adjust your brewing water.

If you’re extract brewing, you don’t generally need to change your water profile. However, it is recommended that you treat your brewing water to remove chlorine and/or chloramine.

Understanding Residual Alkalinity (RA) in brewing water?

Residual alkalinity (RA) is a measure of the amount of alkalinity remaining in water after you establish the initial acid-base balance in the malt bill. It is typically measured in parts per million (ppm). It is a measure of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) equivalents. The acid base is a calculation from the types of malts used. As a brewer, you need to understand the residual alkalinity of your brewing water. Then you can accurately predict the mash pH, based on the recipe you’re brewing.

When water contains dissolved minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and carbonates, it can affect the pH of the water. Carbonate ions, in particular, act as a buffer and can resist changes in the pH of the water.

During the process, your brewing water’s residual alkalinity can have a significant impact on the pH of the mash. The pH of the mash is critical. It impacts the activity of enzymes, such as amylase, that convert the starches in the grains into fermentable sugars (wort).

Adjusting brewing water to suit a beer style

Treat your beer like food and take the following in to account:

- Minerals in the water affect your beer in two ways: pH, and flavour (like salt and pepper).

- Residual alkalinity and malt chemistry combine for mash pH.

- The pH of your mash sets up the final beer pH.

- The pH of your final beer controls the flavour.

All about the mash pH, baby!

If your brewing water’s residual alkalinity is too high, the pH of the mash can be too high (alkaline). This results in incomplete conversion of starches into sugars. On the other hand, if the residual alkalinity is too low, the pH of the mash can be too low (acidic). This results in undesirable flavours, and again, incomplete enzyme activity. Both outcomes result in low conversion rates, with lower than expected gravity readings.

Controlling the residual alkalinity of the brewing water is an essential factor in brewing consistent beer. It is typically achieved through water treatment, or blending with other water sources. Other water sources are usually Reverse Osmosis (RO) or DeIonised (DI) water. DI water is the same as distilled.

Note: Many of us source our RO water from Spotless Water. If you want to get a free £10 when you sign up, click this link to open a Spotless Water account using a referral link. This is a really, really cheap source of RO water. I use it for brewing, and it’s also perfect for other kinds of jobs, such as: car valeting/detailing, window washing etc.

Adjusting your brewing water’s residual alkalinity will give you the best chance of recreating a certain beer style.

Adjusting your brewing water’s RA to suit the grain bill is aimed at getting the mash pH in the right ballpark.

Different beers have different recommended mash pH levels, for instance:

- Pale beers: 5.2 – 5.4 pH

- Amber beers: 5.3 – 5.5 pH

- Dark beers: 5.4 – 5.6 pH

NOTE: Very light beers, such as light lagers, light straw-coloured beers, and golden ales require a negative RA. A negative RA helps pull the mash pH down to the right range. Dark beers have the acidity present in the dark, and roasted malts to buffer higher residual alkalinity waters.

Why do I need to adjust my brewing water to correct the residual alkalinity?

Understanding the alkalinity of your brewing water allows you to accurately adjust it. This allows you to create a water profile to suit the beer you plan on brewing. Once you know the starting alkalinity of your prepared tap water, you can easily adjust it. The remaining alkalinity is used to affect the flavour and other aspects of the final beer.

The residual alkalinity plays a crucial role in the beer making process. Residual alkalinity refers to the amount of alkaline ions remaining in the water after you establish the initial acid-base balance. The residual alkalinity can have a significant impact on the mashing process. And ultimately, on the final flavour, and quality of your beer.

It’s worth noting that the pH of the mash isn’t the only factor that impacts the beer’s final flavour and quality. You need to consider other factors, such as the grains used, yeast strain, and fermentation conditions. These can also have a significant impact.

Residual alkalinity can significantly impact the pH of the mash and the efficiency of the conversion of starches into sugars. This also impacts the final flavour and quality of the beer.

It’s essential to measure and adjust the residual alkalinity of the brewing water to ensure that it’s within the optimal range for the desired beer style.

How can I measure the residual alkalinity of my brewing water?

Note: You need to understand the initial alkalinity of your brewing water (liquor). This allows you to make accurate adjustments for the beer style.

Background

If you’re brewing a pale ale, and your initial RA reading is 250ppm, like mine usually is (Essex water is very hard) then you need to reduce it by around half or more. This allows you to get the best Mash pH. There is more than one way to achieve your aim. You can do this by adding acids like lactic, or CRS. My main aim is always to make as few adjustments as possible. This includes adding the least amount of salts as possible.

Essex tap water is great for dark beers. I can make a stout by simply treating my tap water to remove chlorine. And, other than that, I don’t need to add or remove anything, it’s perfect for buffering those dark, acidic malts.

Preparation steps

I start preparing the brewing water the day before (when I remember). It’s often quoted that it’s best to gas-off chlorine by running any tap water off the night before and letting it stand. You can do that. And it works, as long as you know your tap water only has chlorine added, and not chloramine. To be sure, use 0.5 a campden tablet to remove the chlorine and/or chloramine in your brewing water. To learn about how to treat your tap water, see About Chlorine and Chloramine in Brewing Water.

Note: Chlorine and sometimes chloramine is added to your tap water to kill off bugs. This makes it safe to drink. You need to establish if your water supply uses chlorine and/or chloramine as a steriliser to make your drinking water safe. You don’t want to take either compound through to your finished beer.

Measuring your brewing water’s initial alkalinity

To measure the alkalinity of your tap water, you’ll need an aquarium-type, dropper testing kit, or an electronic alkalinity tester, such as the Hanna alkalinity tester.

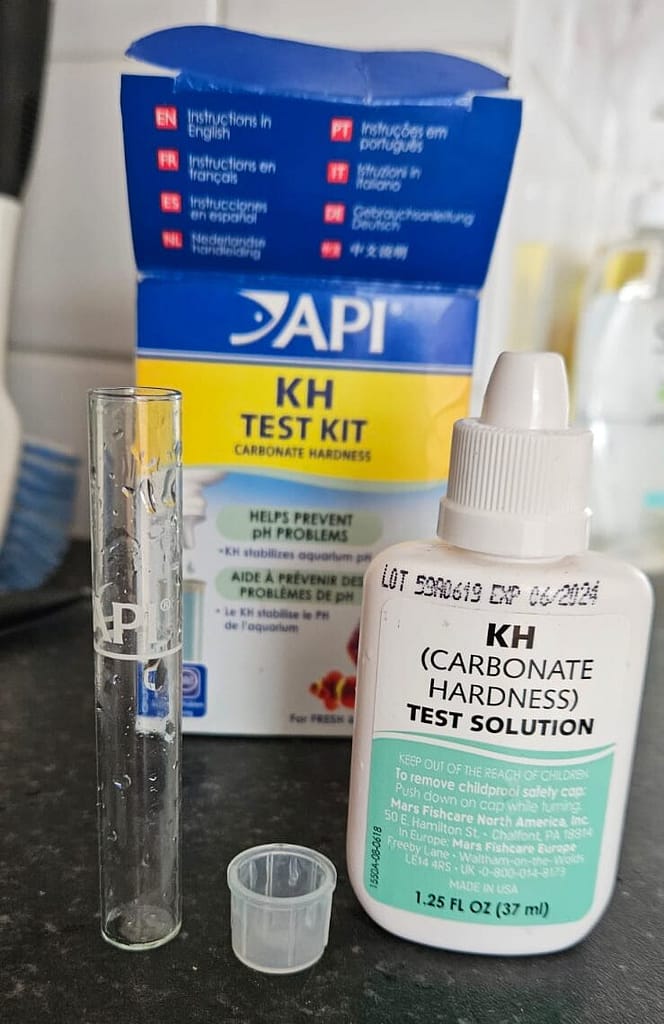

I use an API aquarium KH alkalinity testing kit to test the carbonate hardness. KH is a German unit of measurement for alkalinity. For every drop of testing solution, you multiply the result by 17.9 to get your starting alkalinity. Testing kits are quick and very easy to use.

The kit comes with everything needed:

- Test tube and lid

- Bottle of testing solution

To test the alkalinity of your tap water:

- Fill the test tube to the measurement line with 5 ml of tap water.

- Take the lid off the testing solution and add a drop, then put the lid on the test tube and shake to mix. Unless your water has little to no carbonate hardness, you should see the solution turn a colour, mine turns blue.

- Add another drop and repeat step 2, keeping count of the number of drops used.

- Once you get to the point that the solution changes (mine turns yellow) you can use the number of drops to calculate your water’s alkalinity (carbonate hardness).

- Multiply the number of drops by 17.9 (for this KH kit) and use the answer as your total starting alkalinity.

What do I do now I know my alkalinity?

When you know your initial alkalinity, you can use it to fill in the CaCO3 number in your brewing software. You then use it to help you understand how much you need to dilute your tap water to get you closer to the profile you’re looking for. If you want to drop the alkalinity to a point, say 50% of your starting position. My tap water is pretty reliable at 250 CaC03 alkalinity (13-14 drops of testing solution). However, it can vary depending on the time of year. This is why it’s best to test your tap water before each brew.

How do I know the levels of minerals to add?

I find the 1:1 50/50 dilution rate is a great starting place for a Pale Ale.

Diluting hard, 250 CaC03 Essex, tap water with RO means that I only need to add a small amount of gypsum/chloride.

To understand the salt additions that you’ll want to make to your beer, you’ll need to make choices:

- Do I want the bitterness and mouth feel to be balanced?

- Do I want the bitterness to be more pronounced?

- Do I want the mouthfeel to be more pronounced?

To answer this, you need to understand the effect of adding calcium chloride and calcium sulphate to the water. In short:

- Chloride improves the mouthfeel

- Sulphate increases the perception of hop bitterness

- Both affect the level of calcium in the water – for most beers, aim to hit at least 100 ppm of calcium for yeast health.

A good starting ratio for chloride to sulphate is as follows:

- Balanced: 1:1 (roughly equal)

- More bitter: 1:3 to 1:5 (1 part chloride to 3 or more parts sulphate)

- More mouthfeel: 3:1 to 5:1 (3 or more parts chloride to 1 part sulphate)

Once you plug your water report numbers in to your brewing software, it’ll start to make sense. This ratio is also usually shown at the end of the software, as a report. It usually shows the ratio of these two salts and their effect i.e. balanced, more bitter, or more malty (mouthfeel).

Can I reduce the residual alkalinity of brewing water without diluting with RO?

Brewing paler beers, you’ll need a lower RA to pull the mash pH down to get the best extract possible. You can reduce your RA without dilution, or further reduce it, by playing with acid additions. You can do this with Lactic acid. I generally find that for 23-litre batches (32-33l of total water) that 10ml of lactic works for pale beers. This is added to the whole water, before portioning off the mash, and sparge water.

5g of citric acid also works, but instead, add this to the top of the mash once you’ve doughed in. Citric acid also helps with shelf life stability of your beer, helping to fend off the effects of oxidation.

Understanding your residual alkalinity means you can get a better idea, and fairly accurately predict the pH of your mash.

If you’ve got a water report, you’ll know the levels of the other salts in your water. Now you can add these values to your brewing software and create a water profile. If you don’t know the numbers, you can get a ballpark figure from your local water provider’s website.

My local water is allegedly sourced from 3x different locations. It is then homogenised at different rates, all the time. The RA is usually fairly steady, but can move at any point during the year. Much can depend on the amount of surface water being mixed with groundwater. With this knowledge, I’ve given up trying to predict the salt content. I’ve learned that I can get fairly predictable results by measuring the RA. I can then take the latest readings from my local supplier’s website -(Anglian Water).

NOTE: If anyone local, in the club, does get a water report, and wants to share their numbers. We’re always interested to see if anything has moved.

I’d love to hear your comments on this post and any feedback on how to improve it.

2 thoughts on “Brewing Water Treatment – Residual Alkalinity”